GSoC 2019 - Building A Web Application with Haskell

2019-06-20

For the next couple of months I will be working on the web application issue-wanted for GSoC (Google Summer of Code) and documenting my experience. As I’ve mentioned before, there isn’t a lot of easily accesible material out there for learning how to build web applications with Haskell and I want to change that. A lot of Haskellers that I meet have gotten to the point where they know the basics of Haskell, probably have a few small Haskell projects under their belt, but are having trouble applying their knowledge to a non-trivial, “real-world” application. One of the biggest hurdles that you go up against when building your first big Haskell project is deciding on how to structure it. Unlike OOP, there isn’t a lot of material on functional programming design patterns[1] and how to structure functional programs properly. Haskell is particularly interesting becasue the language is constantly evolving and people are always finding new methods for structuring programs all the time. Should you use mtl-style, free monads, or freer monads?

I’m not sure, but for now there are a two architectural techniques/ideas that I feel like most of the Haskell community can agree are good practices:

I’ll be applying these concepts to issue-wanted with the help of my mentors Dmitrii and Veronika, both of whom have lots of experience in building Haskell projects. Dmitrii and Veronika are the founders of Kowainik, a non-profit organization focused on making the world a better place through well designed software. They’ve a built a wide variety of very helpful Haskell libraries including colog, relude, and summoner. Dmitrii and Veronika also work with Haskell at Holmusk, a health tech company based in Singapore. Issue-wanted is based on a template project used at Holmusk for their web applications called three-layer. The great thing about three-layer is that it avoids the use of opinionated web frameworks, and instead uses a smart combination of well-documented libraries such as servant and postgresql-simple. The three-layer template is simple, modular, and can be moulded to fit the needs of most CRUD applications. Feel free to clone the three-layer repository and play around with it to get a feel for how to apply the techniques used in three-layer to your own projects. For those who need some guidance, I recommend you read the next few blog posts I’ll be writing about building issue-wanted. You can think of it as a case study on building a web application in Haskell using the methods outlined above. I plan on writing about the following topics:

- The Application Monad and ReaderT Pattern

- Using Servant to Define Your API

- Setting Up a Database and Using Postgresql-simple

- Error Handling in Haskell

- Logging for Your Application and Other External Effects

- Writing Tests for Your Application

If you have a solid understanding of the Haskell basics and are looking to understand concepts like monads, monad transformers, and Haskell language extensions in depth then this is the right series for you! I will try my best to break everything down in a simple manner with as little mathematical jargon as possible.

Before I start I would like to quickly summarize what issue-wanted is, and go over some of the design choices me and my mentors made and why. Here’s a short description of what issue-wanted is trying to accomplish from the README.md.

issue-wanted is a web application focused on improving the open-source Haskell community by centralizing GitHub issues across many Haskell repositories into a single location. The goals of issue-wanted are to make it easier for programmers of all skill levels to find Haskell projects to contribute to, increase the number of contributions to open-source Haskell projects, and encourage more programmers to become a part of the Haskell community.

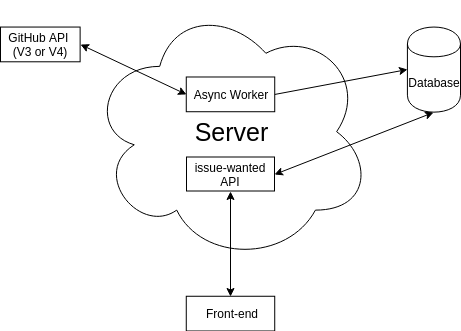

Here is a diagram of issue-wanted’s architecture:

Issue-wanted has five main components:

GitHub API

In order to aggregate all of the Haskell issues and repositories we need to interact with the GitHub API. To do that, we are using phadej’s github library. This library provides functions that are essentially wrappers around the GitHub REST API. They allow us to query the API with convenient functions that take query strings as arguements. For example:

-- | Fetch all repositories with Haskell language and label "good first issue" fetchHaskellReposGFI :: IO (Either Error (SearchResult Repo)) fetchHaskellReposGFI = searchRepos "language:haskell good-first-issues:>0"This function either returns all Haskell repositiories that have at least one issue with the label

good first issue, or anError.At one point we considered using the GitHub GraphQL API (V4), but we thought the github library was to convenient to pass up.

PostgreSQL Database

We will be using a PostgreSQL database to store all the Haskell repositories and issues we get from querying the GitHub API. To bridge the gap between our application and database we will be using the postgresql-simple library. Postgresql-simple is a “Mid-Level PostgreSQL client library” that provides many useful functions for interacting with a PostgreSQL database. You may be wondering why we didn’t go with a higher-level, more type safe, EDSL library like opaleye, esqueletto, or squeal. The reason why is beacuse those libraries are too “powerful” for what we need. Our database schema isn’t super complex, and our most complex queries are basic join statements. Postgresql-simple is great becasue it gives us just the right amount of “power” to do what we need.

Asynchronous Worker

The asynchronous worker will be responsible for querying the GitHub API and syncing the database up with any new Haskell issues and repositories. The details of how the worker will be implemented are still a bit blurry, but it will be scheduled to sync the database regularly to ensure that the most recent issues and repositories are displayed to the user.

issue-wanted API

This is the API that the front-end of the application will be hitting. We easily decided to use servant to define our API endpoints. Servant is a well-documented, battle-tested Haskell library, and is one of the best examples of using type level programming to solve an interesting problem. With servant you can define your API as types and easily compose different APIs at will using the various type operators that servant provides. You then write handlers for your endpoints and then voila! It is not required to understand type level programming in depth to use servant. Here’s an example of simple API route from issue-wanted:

Few things to note here:

The type of our API base endpoint should fill the

routetype parameter in the type signature ofissueByIdRoute.You can think of the

(:-)and(:>)type operators as representations of/in the URL. In this case the URL for this endpoint will be~/issues/:id.Capture "id" Intmeans that the endpoint expects an integer somewhere in the URL. In this case, that integer is the issue ID. Remember, because of theCapture "id" Intin the type signature of our endpoint, the handler function for it must take anIntarguement. I’ll touch more on this below.The last type in the type signature of

issueByIdRoute,Get '[JSON] Issue, basically represents the “return type” of this endpoint.Get '[JSON] Issuemeans that this endpoint takes a GET request and will return a single value of typeIssuein JSON format.

Now that we have defined the endpoint as a type, we need to create a handler function for it. It looks something like this:

Notice, that it takes an arguement of type

Int. This allows us to do something based on the integer at the end of the URL. In this case we simply pass theInttogetIssueByIdwhich is a function that takes an issue ID and returns the corresponding issue from the database. For example;~/issues/49returns the issue with ID 49 from our database.As you can see, it’s pretty straightforward.

Front-End

For the front-end of issue-wanted we are still deciding on what framework to use. The three-layer template project uses Elm, but my mentors and I decided we want to experiment with a different technology. Now, we’re deciding between using PureScript or a Haskell front-end framework like Miso. I haven’t tried Miso yet, but at the LambdaConf hackathon I attended I got the opportunity to use react-basic. It is a library that provides PureScript bindings to React, and I would say it is pretty intuivitive if you have some React experience. PureScript is nearly identical to Haskell so it was a joy to use. Ideally, I would want issue-wanted to be a full-stack Haskell application, but I’ve heard many times that the tooling around GHCJS is a nightmare and getting everything to work properly is pretty much impossible unless you use Nix for package management. This means that if we do decide to use Haskell on the front-end we would have to learn two new technologies: Miso and Nix. This really isn’t too much of a downside for me because I plan on learning Nix anyways and wouldn’t mind getting some experience using it now. This post that I read on r/haskell had some great things to say about Miso and it is definitely something we will consider.

In conclusion, my mentors and I spent a decent amount of time thinking about the architecture of issue-wanted and we are certain it will pay off. We carefully weighed the pros and cons of each design choice and came to the conclusions mentioned above, but nothing is set in stone. There are still some parts of the application that we are unsure of how to deal with for now, but we are confident that the pieces will fall in place as we move along. It is only the third week of GSoC and there is still plenty of room for change. I look forward to working on this project, learning from my mentors, and documenting my experience so that others may build upon it or critique it. Feel free to ask questions, make suggestions or recommendations, or constructively criticize my work by sending me an email at rashad.sasaki@gmail.com. I’m all ears!

Footnotes:

[1] https://graninas.com/functional-design-and-architecture-book/

This book by Alexander Granin is looking to change that. I’ve read some of the sample chapters, and from what I’ve read it seems like a good book for learning more about these sort of ideas. I believe there are also some books by Graham Hutton or someone else that discuss the architecture and design of functional programs, but I’m not sure how good or relevant they are.